The Use of Women’s Empowerment as a Marketing Tool

If you’re a younger Millennial or older Gen Z, themes of women’s empowerment have been omnipresent in the marketing of products sold to women. The varying shades of the bold red lipstick has been sold as a confidence booster for quite a long time, since before the generations I listed even existed. While it isn’t strange for messaging around men’s products to emphasize masculinity and women’s products to emphasize femininity, there is something a little different about the brand of femininity highlighted in beauty products.

I took a look at older ads for women’s perfumes to understand how advertising has transformed with changing perceptions of gender and women’s role in society. We begin with older advertisements that focused on beauty and traditional femininity.

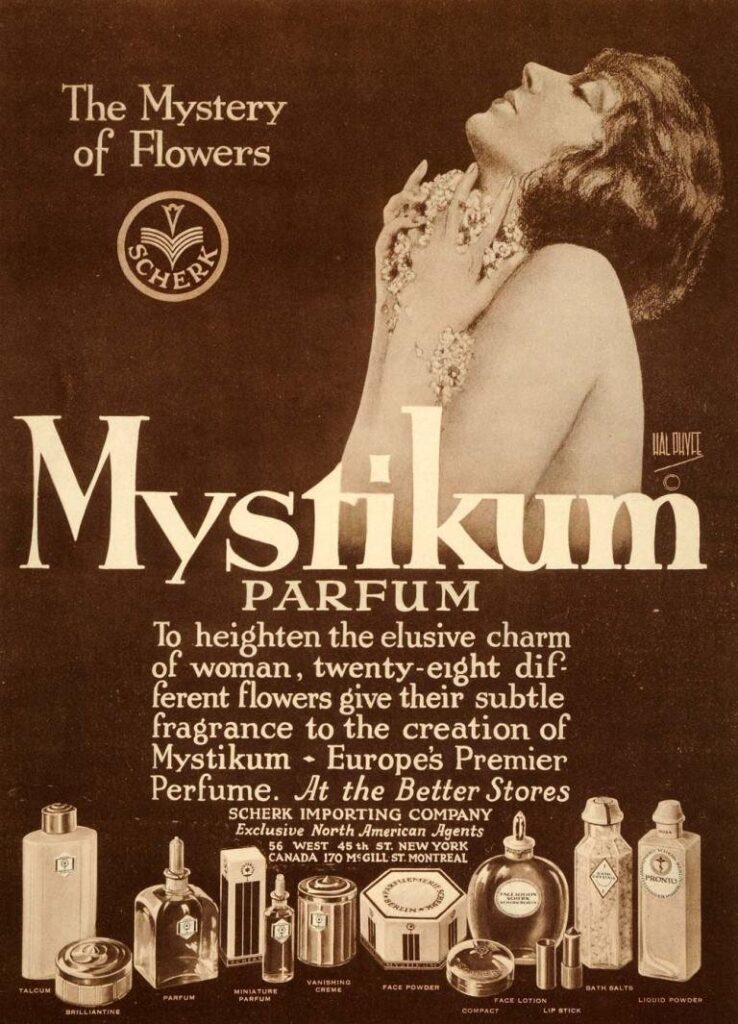

Mystikum Parfum (1920)

This ad relies on the age-old depiction of women as mysterious creatures who cannot be understood. An excuse, if you ask me, to never put in the effort to understand a woman as a full human being who doesn’t neatly fit into their box of womanhood or femininity. When you label a people as too erratic (emotional) to be understood, you get to ignore them or project your own conceptions of them onto them with little resistance.

The focus is on femininity with the emphasis on the 28 flowers that went into the making of the perfume. They also make sure to reassure the market that the scent is subtle. While this is in service of describing the perfume itself, it can also be seen as a reaffirmation of the right kind of femininity– subtle. Quiet.

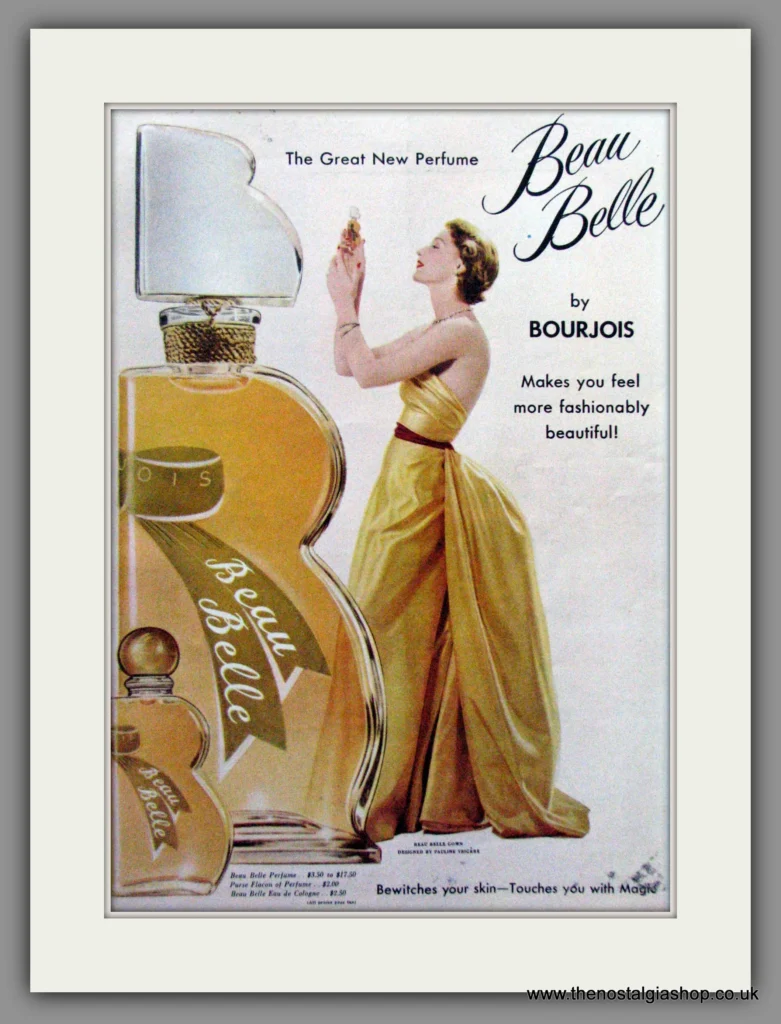

Bourjois Beau Belle (1949)

The ad is quite simple– a beautiful woman in a beautiful dress the same color as the perfume being advertised. With the sense of smell hard to translate for the visual medium, they stick to saying the perfume ‘Bewitches your skin– Touches you with magic. A perfume that makes you feel fashionably beautiful.

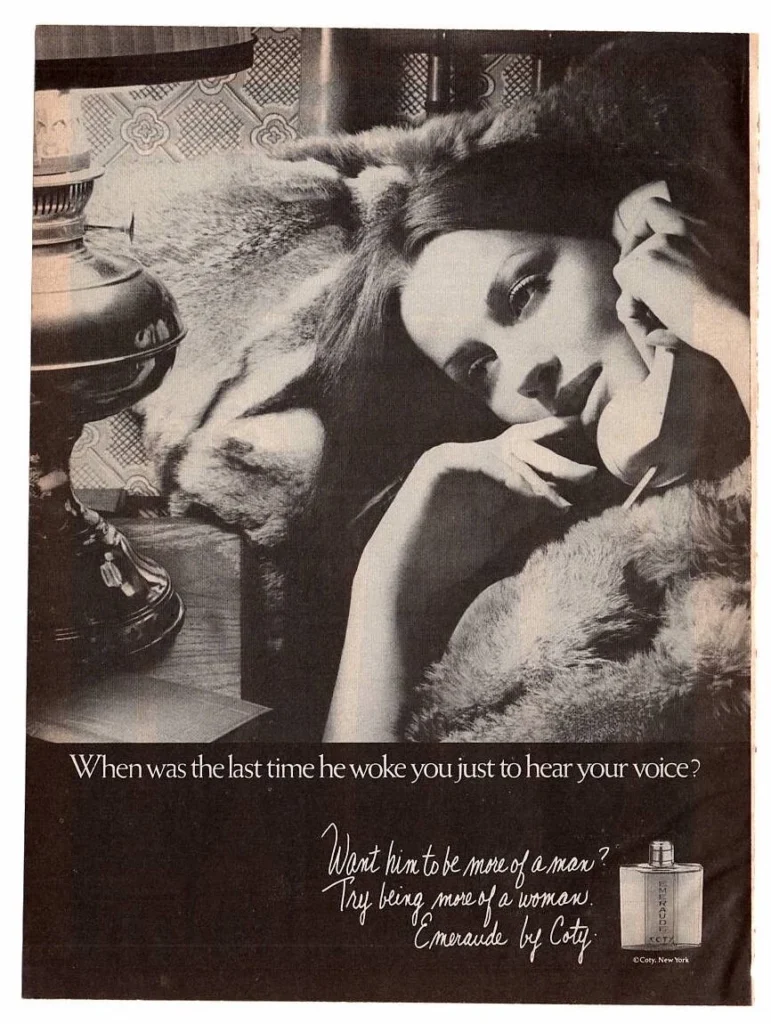

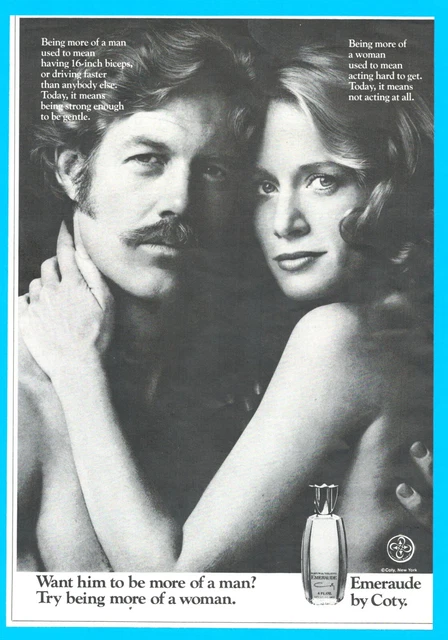

Coty Emeraude (1970s)

This one pulls no punches advertising their perfume as something that could earn a woman attention and affection from a man. It puts the onus of fostering a romantic relationship on a woman being as feminine as possible– by buying a product sold to her. It draws rigid lines around masculinity and femininity, reinforcing the genders to play their part. The actions of a man, whether or not he is man enough, is made the woman’s responsibility.

There are other ads in the same campaign that attempt to convey a more complex perspective on gender roles. It is an indication of changing times. A rethinking of gendered life. Yet it exploits women’s insecurities about fitting into society’s definition of ‘woman’ and sells them a product to ‘fix’ themselves. We can see the beginnings of the modern era of advertising in such ads.

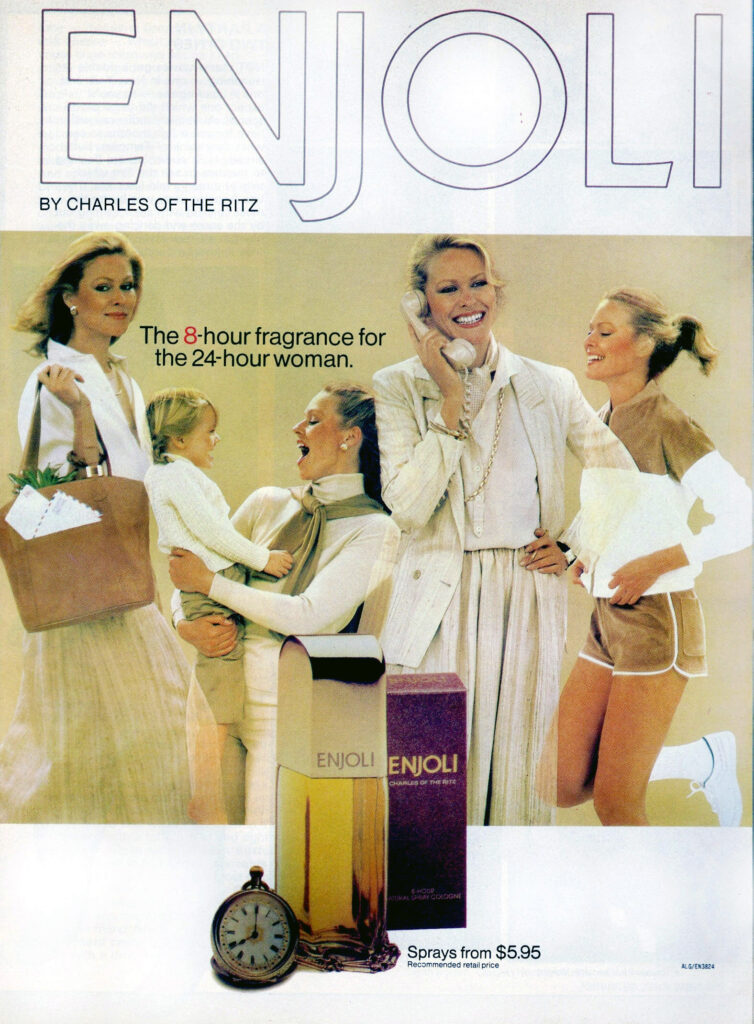

Enjoli by Charles of the Ritz (1978)

The ad caters to the working woman who does it all. We see her indifferent outfits, different roles as a woman, throughout the course of a day. She’s looking fashionable, buying groceries, being a mother, answering phone calls at work, and being athletic. ‘The 8-hour fragrance for the 24-hour woman’ is a banger from the marketing perspective– highlighting the longevity of a perfume and acknowledging just how hard your consumer base works. Acknowledging all the work, a population that doesn’t feel seen created a connection that can prime them to buy your product.

While the ad recognizes women’s role in society– their 8 hours of paid work outside the home and the remaining 16 hours of unpaid work at home– it leaves a bad taste in my mouth that the ad does it in service of selling something to women. Women’s hard-fought economic independence becomes a simple marketing tool to sell a beauty product.

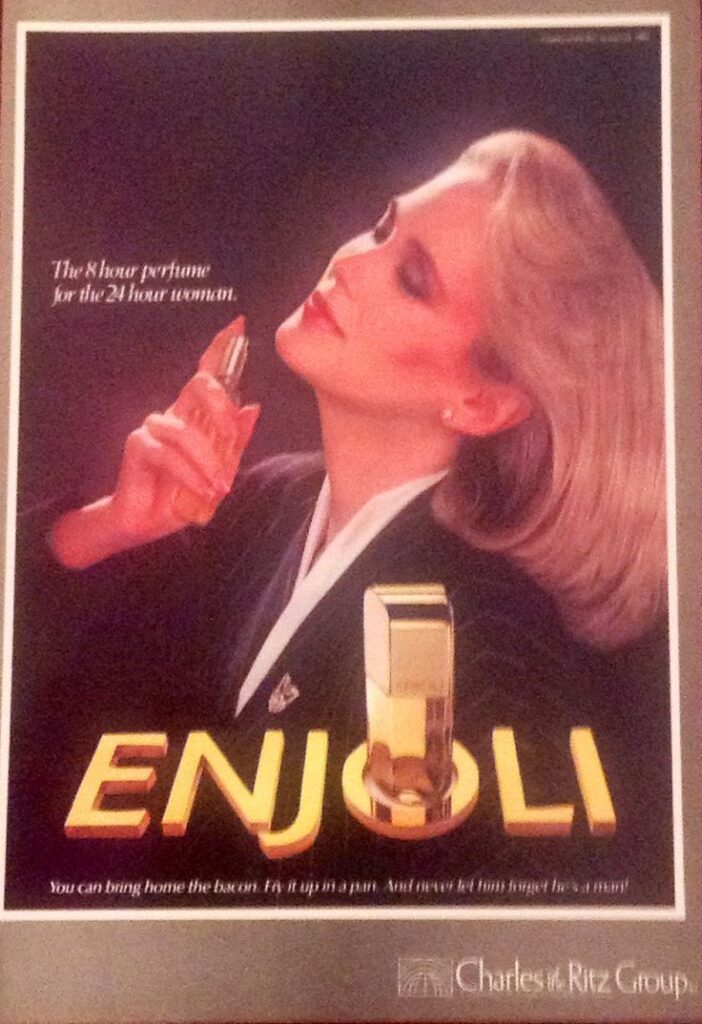

Another ad from the same campaign tells women that they may be breadwinners of their families, but their work is still not done. Bringing money home is enough for men to not contribute anything else to the household. But women are expected to bring food home, prepare it, and also bear the responsibility of soothing the burns that may cause a man’s ego. All that work all day and she must still go home and labour for free while making sure a man feels like a man, whatever that is supposed to mean.

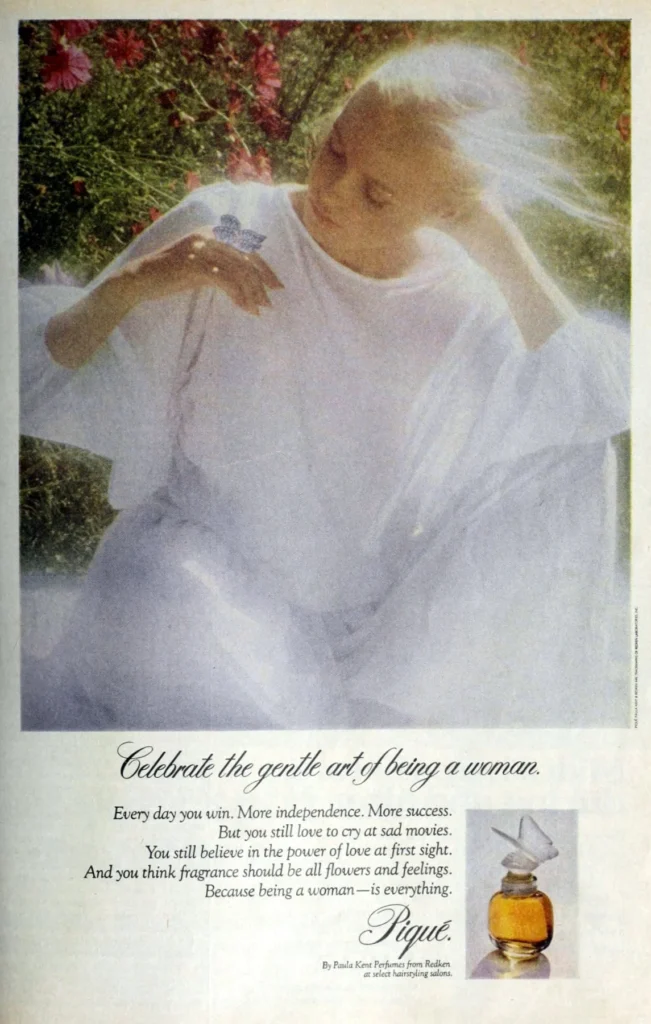

Pique Paula Kent (1970s)

This ad is grasping at the straws of traditional femininity that restricted women to beauty and fragility. It’s a ‘you can have it all’ reassurance to women who are succeeding in life in their own right and not having to depend on a man– probably the first women in their lineage to achieve this. Such independence comes at the cost of social disapproval. The ad reassures women that though they are being ‘unfeminine’ enough to be independent, they are still woman enough because they perform other kinds of femininity– crying at movies, believing in love at first sight, and that fragrance should be all flowery and about feelings.

It essentially preys on women’s complicated feelings about attaining some power through economic independence to sell them femininity in a bottle. It says ‘yes, you’re a big girl and all but you must still be pretty’.

Women’s Empowerment as a Marketing Tool Today

It first struck me when I was reading Dior’s description of the Miss Dior Essence de Parfum. A bit too late to have the realization, I must admit.

Dior describes the perfumes as:

‘A symbol of confident, liberated femininity imagined by Francis Kurkdjian’.

The statement is quite vague about how the perfume and its composition represent confident and liberated femininity. I’ll have to take their word for it. They go on to make this statement in the same page:

‘Hyper-feminine, the Miss Dior essence de parfum becomes the manifesto of a new generation of women freed from social conventions, and who call the shots.’

A statement that begins and ends by contradicting itself. It tries to play both sides and fails miserably at it, ending up with a word salad that means nothing. What does women’s liberation mean to Dior? When they speak of ‘confident, liberated femininity’, what is it that they speak of? Clearly not the actual meaning of women’s liberation.

We have been fighting tooth and nail for a world where they can be more than their physical beauty. Everyone, male or female, likes being and feeling beautiful. There’s a reason male birds have the colorful plumes they do and the dances they perform. But that’s as much credit as I am willing to give to pure biology. A lot of the rituals– both the innocuous (wearing makeup, using perfumes) and the extreme (starving yourself for the perfect figure, invasive surgery to fit into the latest trend for the female body) – stem from the need to fit in. To perform femininity, whatever it takes, to be accepted by larger society and our closer social circles.

Women who aren’t pretty enough, who don’t fall in line and be appropriately feminine are punished for it. Ask activists who have been they’re only fighting for women’s rights because they’re bitter about being ‘too ugly’ or too fat and unable to get a man, as though that is any achievement at all.

There is no liberation in prettying yourself up with a perfume or a blush. Beauty rituals are fun. I enjoy wearing lipstick and painting my nails and spraying on sweet perfumes. But I am painfully aware of the fact that while I derive joy out of these rituals, I don’t do so in a vacuum. I exist in a society that has told me since childhood that being adequately feminine is the most important thing I will do as a woman. A lot of the performance of femininity comes from the fear that I will be punished for not being woman enough.

The beauty industry would crumble tomorrow if we all woke up and decided that we didn’t care about being beautiful. But no woman wants to be the first to decide that. We have seen what happens to those women, we have meted out punishment ourselves. So we fight to stay the young, hot objects we are supposed to be, slather on anti-ageing products from the age of ten whether or not we know better.

It is vile that brands, not just Dior, use this injustice against women to sell products that contribute to women’s insecurities of not being the prettiest object for our social survival in order to sell us something.

Hyper-feminine, Dior calls this perfume, before going on to say it is the manifesto for women who have been freed from social conventions. I would laugh if it wasn’t infuriating. How is it breaking free of social conventions to spend one’s money to perform femininity? Calling a product of all things a manifesto for women’s liberation is simply a mockery of all that women go through to make the hard-earned money they use to buy a 50 ml bottle of perfume for AED 655. The workplace continues being a place of performance of femininity.

Sure, no workplace requires that you wear make up and a Dior perfume. But all women know that you’re more likely to be taken seriously at the workplace if you look good. The very economic independence that allows us to buy beauty products is contingent on our performance of beauty.

I am dogpiling on Dior here (oh no, won’t anyone think of the plight of the megacorporation!), but other brands aren’t guiltless in this, advertising their women’s fragrances so:

Narciso Rodriguez All of Me

“All of Me by Narciso Rodriguez parfums is a multi-faceted fragrance created for a new generation of women, who confidently embrace all that makes them unique – their beauty, their grace and their power.”

Prada Paradoxe

Speaking about the bottle design, Prada Creative Director Coralie Salem says she designed the bottle to represent the paradox that was the Prada woman.

“I really wanted to bring a very minimalist touch, very radical. I wanted to show contrast between sweetness and the toughness because this is also part of the Prada woman. It’s a form of determination, but with a lot of delicacy.”

YSL Libre Vanille Couture

“A reflection of the LIBRE woman’s own radiant spirit. For her, freedom is gold. She lives and breathes her freedom, igniting her own destiny, defining her own rules.”

Carolina Herrera

“Good Girl is a daring yet sophisticated fragrance inspired by Carolina’s unique vision of the duality of the modern woman.”

All these products and their brands talk about women’s freedom and independence. But at the end of the day, they are selling us something. Once upon a time, they were selling us attention from a man, selling us beauty. While that was bad for women’s empowerment in its own way, I much prefer it to corporations selling us women’s empowerment through the performance of gender roles.

Before women had jobs, and hence the disposable income, advertising was geared towards men. Now that women control their purse, products are advertised to us. That is all we need to know about brands’ big talk about women’s freedom and liberation. All that matters is our freedom to buy their things and if it means making you feel less feminine, less attractive, so be it.

Nothing wrong with wanting to be pretty (I am painfully aware I’m issuing this disclaimer out of fear of being called an ugly hag who is jealous of the pretty girls for having fun and getting a man). But remember that your disposable income is a historically recent privilege.

Men don’t spend such a large percentage of their income making themselves desirable to you. You can make yourself feel better by calling your expensive beauty routines a choice. Technically, it is. But it’s only women who are told fairytales from childhood about accepting a Beast for his heart of gold. You can and do choose, but none of your choices are made in a vacuum unaffected by the patriarchy.

Calling it a choice only makes you feel less guilty about being a ‘bad feminist’. A guilt that brands will exploit to sell you their feminist lipstick and their feminist handbag and their feminist perfume at high profit margins.

I don’t want my perfumes to be #Girlboss. When I want inspiration out of perfumery, I’ll look at the women who have excelled in the industry.